Trecho da notícia e comentários em vermelho: O maior vírus do mundo foi descoberto por pesquisadores da Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais (UFMG). Chamado de tupanvirus, ele não faz mal a seres humanos e pode, no futuro, ajudar a diagnosticar várias doenças.

Amostras de sedimentos da Bacia de Campos, no Rio de Janeiro e de lagoas salinas no Pantanal, em Mato Grosso do Sul, foram analisadas em laboratório. “A gente nunca imaginava que pudesse ser tão diferente, que pudesse ser tão grandioso o vírus que a gente conseguiu isolar. Então, assim, foi sensacional ver pela primeira vez aquele vírus todo diferente, com uma cauda, que nunca tinha sido descrito, daquele tamanho”, disse a pesquisadora Thalita Arantes.

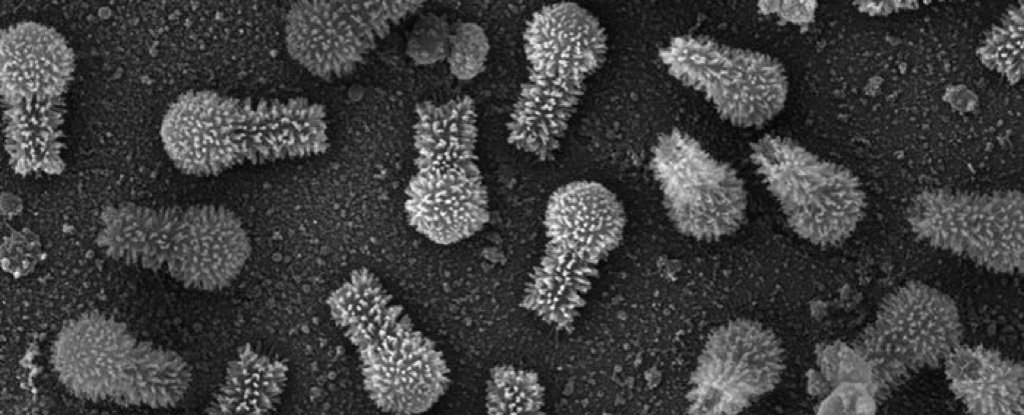

Os supervírus são os maiores já encontrados no planeta. São dois muito semelhantes e que parecem microfones peludos. A descoberta foi publicada na revista científica britânica Nature Communications. “Quando nós fizemos o sequenciamento completo, nós percebemos que, além da estrutura, que já era fantástica, o genoma era fantástico. Codificava genes (proteínas, né?) nunca vistos antes no planeta. E cerca de 30% dos genes eram completamente novos”, disse o professor Jônatas Abrahão, professor pesquisador da UFMG.

Segundo os pesquisadores, os novos vírus chegam a ser 50 vezes maiores que os comuns. Os da dengue, zika e febre amarela são pequenininhos como uma cabeça de alfinete (Péssima frase. Os vírus são muito muito muito menores que uma cabeça de alfinete. Só são visíveis ao Microscópio Eletrônico.). Depois de três anos de estudo, a equipe descobriu que esses gigantes têm carga genética complexa, o que é de grande interesse científico (Carga genética é um termo incorreto. O correto seria dizer informação ou conteúdo genético. Carga genética se refere ao conjunto de genes "ruins" ou deletérios presentes em um organismo.).

Os supervírus são capazes de produzir proteínas, elementos biológicos bastante usados na identificação de doenças. (Ops... capazes de produzir proteínas durante o ato de parasitismo, né? Usando a maquinaria de síntese da célula hospedeira. Se produz proteína sozinho, então não seria um vírus.) Esse é o próximo passo da pesquisa do tupan.

“A produção de proteínas é importante pra uma série de testes de diagnóstico pra doenças infecciosas. Então, alguns testes por exemplo pra detecção de anticorpos em pacientes que já tiveram dengue, já tiveram zika ou até mesmo febre amarela muitos são baseados na presença de proteínas”, explicou o professor Jônatas Abrahão.

Os pesquisadores alertam que ninguém precisa ter medo do vírus gigante. Já está comprovado que ele não infecta seres humanos, e é uma grande conquista para a ciência.

LINK em inglês sobre o assunto: www.sciencealert.com/giants-viruses-discovered-brazil-among-largest-most-complex-ever-found-tupanvirus-mimivirus

TEXTO DO LINK ACIMA (Texto bom para uma prova da Faculdade de Ciências Médicas, por exemplo.)

These Viruses Found in Brazil Are So Huge They're Challenging What We Think a 'Virus' Is

This could change everything.

Scientists have discovered two new kinds of virus in Brazil that display such size and genetic complexity we may need to rethink exactly what viruses are, scientists say.

The two new strains – dubbed Tupanvirus, after the Brazilian thunder god Tupã in Guaraní mythology – are as prodigious as their namesake, and while they're not a threat to humans, their existence further challenges the scientific boundaries that define what a virus is.

Tupanvirus soda lake and Tupanvirus deep ocean, both named in relation to the extreme aquatic habitats in which they were discovered, aren't just among the largest viruses ever found – they also contain the most protein-making machinery of any virus discovered to date.

The strains, whose optically visible tailed forms can reach lengths of up to 2.3 micrometres, comprise some 1.5 million base pairs of DNA, with enough protein-coding genes to produce up to 1,425 kinds of proteins.

In terms of protein synthesis, this gives them the "largest translational apparatus within the known virosphere", explains a research team led by virologist Bernard La Scola from Aix-Marseille University in France.

This apparatus puts Tupanvirus in the virus family of Mimiviridae, named after Mimivirus, which was identified in 2003 - at the time it was the virus with the largest capsid diameter ever discovered, among other notable attributes.

Before Mimivirus, viruses were largely considered wholly separate from 'living' creatures, with their inability to synthesise proteins (and thus produce their own energy) being one of the reasons scientists excluded them from being classified among cellular life.

But Mimivirus's genetic complexity – and that of other giant viruses that have subsequently been discovered – challenges this theoretical boundary, because they carry genes capable of things like DNA repair, DNA replication, transcription, and translation.

"With the discovery of superviruses, we have seen that these genes may be present in viral genomes," one of the team behind the Tupanvirus study, Jônatas Abrahão, told Brazilian newspaper Estadão in Portuguese.

"This characteristic changes the notion we have of the distinction between viruses and organisms formed by cells."

And the more we learn about giant viruses, the more we learn what they're capable of.

The Tupanvirus strains don't just hold a (nearly) complete set of genes necessary for protein production – about 30 percent of their genome is unknown to science, being as yet undiscovered within the domains of archea, bacteria, and eukarya.

Obviously, there's still a lot to learn about Tupanvirus and giant viruses in general, but the good news is, this new entity – whatever it exactly should be classified as – is no threat to humans, only amoebae.

But if you're an amoeba, we have bad news.

"Like other giant viruses that have been discovered in the past, Tupanvirus infects amoebae," Abrahão says.

"The difference is that it is much more generalist: unlike the others, it is capable of infecting different types of amoebae."

The findings are reported in Nature Communications.

Nenhum comentário:

Postar um comentário